Photo: Gerhard Maurer

Architectural Icon / Piranesi 46/47

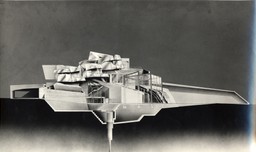

Steinhaus, Steindorf am Ossiacher See, Austria, 1986-2008

Günther Domenig

DIMENSIONAL, About Günther Domenig’s Architecture

by Andreas Krištof

“How big does a building have to be to be called a monstrosity by its enemies and an opus magnum by its friends?”

Anna Baar: Günther Domenig: Dimensional. In Resonance. Jovis, Berlin 2022.

The starting point of the present essay is the exhibition project Günther Domenig: DIMENSIONAL, Structures and Shapes, which for the first time at four venues in Carinthia comprehensively and contextualised by way of contemporary artistic and architectural positions showed the work of the internationally renowned architect born in Carinthia.

The complex exhibition and research project attempted to reposition the work and the person of Günther Domenig, and to update it.

The four exhibition venues stood for different aspects of Günther Domenig’s work, just as they were presented in different ways. While the Museum of Modern Art Carinthia (MMKK) explored the relationship between art and architecture, the Architecture House Carinthia focused on the impact on contemporary architectural production. On the other hand, the Domenig Steinhaus (Stonehouse) in Steindorf on Lake Ossiach and Heft in Hüttenberg were exhibition objects themselves, and were directly activated by artists, architects and performers.

Accordingly, the text contribution is also based on the thematic structure of the exhibition and evolves, beginning with biographical history, continues with the reactivated, the utopian and the physical to the manifest. The Stonehouse can also be found in the manifest, which is central to making Domenig’s understanding of architecture visible.

Despite Günther Domenig’s international relevance for the development of architecture – his radical design, which represents a turning point in dealing with building traditions and conventions and anticipates developments – his work is currently little noticed and little researched.

Much of what Günther Domenig’s architecture stands for, much of what characterises his ambivalent person – and what Anna Baar describes so wonderfully in her essay, published in the accompanying book In Resonance, can be understood a little better with the knowledge of his biography.

Günther Domenig was born in Klagenfurt in 1934. He spent his childhood in the Moll Valley, a narrow valley in Upper Carinthia surrounded by high mountains, where he lived until 1946, and thus during the Second World War, interrupted by summer stays with his grandmother on Lake Ossiach.

The central motif of his architecture developed here: the rugged mountain landscape with the diverse rock formations, which is central to the construction of the Stonehouse – a fusion of organic and inorganic architecture.

Domenig was born into a Nazi family. His father was a district judge in Klagenfurt and a member of the Nazi Party. In 1944, he was seized by partisans in Trieste and executed. His mother was also a functionary in the Nazi Party.

As a result, Domenig developed a resistance that manifests itself on many levels by, among other things, opposing all architectural conventions of the post-war period, defying a specific form of use and questioning social norms. Throughout his life, he struggled with his family background and became a dedicated anti-fascist. His reconciliation with his own family history only happened with the project for the Documentation Centre Nazi Party Rally Grounds in Nuremberg, which is a ruthless intervention in a historically highly charged inventory. Intervention and resistance became a persuasive unit and, as Peter Noever aptly puts it, “the manifesto of artistic ethics”.

“I think if anyone can be considered a forerunner of Zaha Hadid’s architecture, then it is Domenig. And if an Austrian architect followed Kiesler, then it was Domenig. And if anyone deserved to receive the first Kiesler Prize, it was Jørn Utzon for his Opera House in Sydney, and then the second for Domenig.“ Jan Tabor, architecture critic