Photo: Miran Kambič

Architectural Icon / Piranesi 44/45

Kanin Hotel, Bovec, Slovenia, 1969-1973

Kanin Hotel in Bovec, Original Critical Regionalism of the 1970s

by Aleksander Saša Ostan

In the early 1970s, on the border of the picturesque market town of Bovec, the architect Lajovic designed a modern hotel building, abstractly inspired both by the geomorphology of the Kanin mountain range and by elements of the traditional Bovec house, thus becoming one of the heralds of critical regionalism in Slovenia.

Approaching Soča, Bovec and Kanin: the hotel’s position in the settlement organism

From its source in the Trenta Valley, the clear, turquoise and vibrant Soča River flows into the Bovec basin as a natural and cultural phenomenon that transcends borders, prejudices and fears. The aorta of the Soča Valley, it carries with it everything material and spiritual that it has ever touched: from joyful to painful memories, from adrenaline to therapeutic vitality… As Heraclitus of old would have proclaimed: everything flows, “panta rhei”, adding that no man can step into the same river twice.

After leaving the narrow Trenta Valley and entering the Bovec basin, an inaccessible cliff rises just above the confluence of the Soča and Koritnica rivers, and above it, there rises the small hill of Ravelnik, the site of a prehistoric hillfort. Today, the place features an open-air museum dedicated to a fortification line from the First World War, and the hillside descends over a gentle slope and past the remains of a Roman settlement towards the Bovec field and finally climbs up the field path past the Gothic Church of the Virgin Mary in Polje towards today’s Bovec. An important spatial and temporal axis with rich visible-invisible traces, along which we also find the Kanin Hotel on the southern edge of the settlement.

Bovec is nestled on the gentle edges of the southern slopes of the mighty Rombon, along the Neolithic route between the Adriatic Sea and Carinthia. Below the town, the wide plateau of the Bovec field opens out to the south (while the Soča remains below the geological fault on the lower terrace), from which Bovec is perceived in a most archetypal way: the settlement has found its position at the intersection between the scree of the Rombon and the lowlands of the field, organically adapting itself to the conditions of transition from the landscape’s horizontal to its vertical. Among the settlement’s key landmarks – viewed from the south – the dark silhouette of the Kanin Hotel appears in the foreground of the broad landscape view: the volume lies above the pastures that rise gently towards the settlement and on which sheep still graze today.

The spatial axes of Bovec in relation to the hotel and its geomorphology

Bovec has two main spatial axes, which meet at right angle in the very centre of the town, on the main square or Plac. The longitudinal, horizontal axis is the traffic axis, this is where we enter Bovec. The road winds through the town and follows the old route that once connected Gorizia and Carinthia via Predil mountain pass (the “material axis”). Perpendicular to it, there is the vertical, pedestrian axis of the town (already outlined in the introduction), linking the two churches of Bovec, the dominant St Urh on the hill above the square and the Gothic Virgin Mary in the grove in the Bovec field (the “spiritual axis”). Two archetypal spatial and semantic principles make up the basic orientational and identification skeleton of Bovec: above and below, exposed and hidden, masculine and feminine, external and internal, immanence and transcendence, all the elements complementing each other beautifully.

When one approaches the Kanin Hotel, which forms the southern urban boundary of the town (otherwise defined by the old dry-walls, the “miri”, behind which lie the gardens and orchards of the townhouses), along the axis or path from the direction of the Virgin Mary, the hotel is almost miraculously complemented in the background by the silhouette of its namesake, the Kanin mountain range, which separates the Bovec Valley from the valley of Resia on the Italian side of the border.

The image of the building derives from the geomorphology of the Kanin mountain ridge, which – compared to the domed Rombon – is experienced as a long but rhythmic, dramatically rocky silhouette.

It is as if the architect of the large volume of the Kanin Hotel and its positioning in space had meticulously painted the pattern of this architectural composition, to manage to place it so precisely in the field of direct dialogue with this mighty mountain. The fractal self-similarity as a principle of harmony between “nature and culture” proves in this case to be the optimal answer to the creative dilemma of forming the edge of a settlement with a large, modern architectural volume. In this context, the building with its slope and terraces, which now grows organically out of the green meadows like a large standalone landmark or a boulder, would look rigid, alien, too urban if assuming a pure Euclidean form (a cube, square or cylinder).

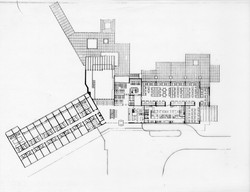

The house also evokes a modern “city wall”, which rises suddenly and at a gentle inclination from the green meadows, its convex shape more “defensive” on the outside and concave and more “protective” of the settlement on the inside. Looking at the ground plan, the large longitudinal mass of the building breaks off somewhere in the middle, where the entrance to the hotel is also located on the city side. This compositional approach reminds us of the Prisank Hotel. In this way, the building is optically reduced and segmented to create complex conditions for a range of interesting views of it, clearly legible from virtually all sides.

The complete interview is published in Winter 2021 issue of Piranesi No. 44-45/Vol. 29.