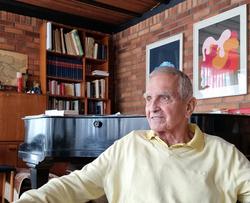

Photo: Robert Potokar

Interview / Piranesi 44/45

Interview with Janez Lajovic

Poetic Regionalism

by Robert Potokar

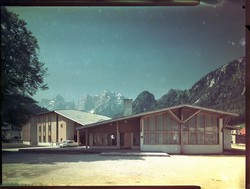

The architect Janez Lajovic, born in 1932, belongs to the oldest generation of architects who studied with Professor Edvard Ravnikar and began, in the early 1960s, their independent creative paths in their own architectural offices. His career was extremely successful, as more than fifty projects were built according to his designs. His two hotels, built in harmony with the Alpine environment, the unfortunately demolished Prisank in Kranjska Gora and the Kanin Hotel in Bovec, are even today still considered to be the best examples of hotel architecture. He received several accolades for his work, including the Yugoslav Federal Borba Award for the Kanin Hotel in 1974. His works were showcased in various galleries, but we are still waiting for a major exhibition and monograph on his work, such as he truly deserves.

Despite his venerable age, he is a more than lucid interlocutor on architecture, spatial issues, art and lifestyle. This interview took place in November 2021, after he had returned from a hospital and spa where he went for rehabilitation treatment. In our conversation, we present the life path of the creative architect and engineer, a path he shared with his wife Majda Dobravec Lajovic, or Gusja, (1931-2020), with whom he lived and collaborated for almost sixty years.

Studies, architectural work

Piranesi: By way of introduction, I would like to ask what inspired you to become an architect. Did you know from a very young age that you wanted to work in the field of construction and culture at the same time? What was that decisive shift in your mind that made you decide to become an architect?

Janez Lajovic: Not from a very young age, but at the age of 15 or 16 I was already quite determined that architecture was the right thing for me. I had a very keen interest in it. I don’t know why, but I thought it would be interesting for me, and it’s stayed that way. It did not take me long to decide, nor did I hesitate. After graduating from classical grammar school, I went straight to university. I felt that this was it. It’s worth mentioning that I had a great teacher at school, Alenka Gerlovič, a painter who knew how to present art to us in a broader way.

What was the study of architecture like in the 1950s?

The subjects in the first year were mostly technical, that was until the third year, and only later did you decide which professor to do your seminar with. In the first year you worked with Professor Valentinčič on freehand drawing of classical architecture, drawing Ionic, Doric columns with a hard pencil, while in the second year our tutor was the architect and painter Boris Kobe. All of these side subjects were like a pre-course for the third year, where in the first semester you went to Professor Edvard Mihevc, and in the second semester to Professor Edvard Ravnikar. With Mihevc I designed a modern single-family house, we had quite a few discussions, but when I came to Ravnikar I realised that his was a completely different level and a different understanding of architecture. That’s why I decided to continue with him.

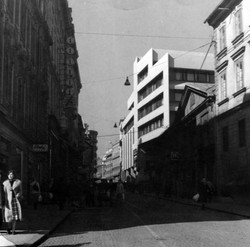

You graduated in 1957 under Professor Ravnikar, with a topic that is relevant even today, yet still seems unrealistic: deepening the Ljubljana railway junction to make it run underground. This is a topic that you continued to work on in later years. How is it possible that, sixty years on, we are still wondering whether it is even feasible, calculating how much it would cost, and rhetorically noting what Ljubljana would gain from it?

My colleague Tone Pibernik had a regional plan for the whole of central Slovenia, and I was working on the railway and the problems of how to incorporate it in the city. I came to the conclusion that the only sensible way to do it was the way it’s done in many cities, for example in Copenhagen, when you get to the centre and you don’t even know that you’ve taken the railway. The station and everything else is on the lower level. You’re in the city and there’s virtually no railway, while in Ljubljana there’s no city but there is a railway. I don’t know who is questioning the deepening project. Certainly those political parties who’d prefer to see somebody else pay for it. But sooner or later we will have to do it ourselves.

Let us say a few words about Professor Ravnikar, who is considered to be a central figure in Slovenian architecture of the second half of the 20th century. He probably had a decisive influence on you and other students during your studies and even after graduation. Can you describe your relationship, or maybe you have an anecdote to tell from your studies?

What makes Ravnikar so special? Because he would always ask why and how to do something. Not where he could get a pattern. He taught us to think – and I am still thinking that way even now – about how to do something. You can see that if you look at what is happening in the car industry right now with Elon Musk. He is asking himself how to get to something as cheaply and as quickly as possible. In the end, the difference is that it takes Volkswagen twenty-five working days to make a car and Tesla only ten days. 10 : 25. That is the difference.

Ravnikar was not one of those who would say this is good or bad, try a little bit like this, left or right. He would bring you a little booklet about something completely different. If you read it, you slowly understood what he brought you and what he wanted to say. You saw that his primary aim was to make you think.

Maybe I can describe the work and the atmosphere in the seminar, it was all hustle and bustle, conversation, you could ask his assistants for advice. Behind me was Savin Sever, who was at that time designing the project for the municipal building in Kranj. So I was involved in conversations, in reflections, which often led to in-depth discussions.

As a student in the 1950s, you had the opportunity to meet the then elderly Professor Plečnik. What did you and your fellow architects think of his work at that time? You probably thought his approach was backward-looking and far removed from the spirit of the times represented by the new social order and, of course, modern architecture.

One could set one’s watch after Plečnik. He arrived at 8 a.m. sharp, and my fellow students and I used to joke we would go and see if it would be the same that day. At that time, we were looking at Corbusier, Niemeyer, Mies van der Rohe – the modern architects of the time – and Plečnik, of course, seemed to us like from another planet. Then, as students, we would walk around Križanke, especially the inner courtyard, which, despite the decoration, makes sense, and we saw that it was not done for nothing. You can see a different attitude towards the materials. I think that Plečnik – and then also Ravnikar – conveyed to us above all the awareness that space, every square centimetre of it, is precious. Then there are his visions of seeing something from a distance, a nice example of that is the erection of Napoleon’s Column and the layout of Vegova Street, all the way down to his house in Trnovo. I had not thought about that before. But the one who really said something about Plečnik was Ravnikar. He reminded us that it was not just about decorations, that everything had a meaning.

On the other hand, it’s true that fortunately many things were not realised according to Plečnik’s ideas, because in that case half of old Ljubljana or at least part of Ljubljana Castle would have been demolished.

A few years later, your studies led you to the USA, where you received your Master’s degree from MIT, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in 1967. At that time, only a few architects were given the opportunity to continue their studies in the USA, one of them being Vladimir Braco Mušič, for example. What did studying in the US mean to you? I suppose, above all, broader horizons and greater open-mindedness.

I was lucky. When the Prisank Hotel was completed, it was automatic. I didn’t apply for anything, I don’t recollect how it came about. I was in the US for a little more than a year. Two semesters in college, on a Ford Fellowship, and another three or four months travelling around America with Gusja. I bought a Chevrolet station wagon for the trip. We put the mattress we had slept on for the whole semester in the car, and there was still room for a mini kitchen. So equipped, we travelled all the way to Vermont, through Montreal, where the Universal Exhibition was, to Niagara Falls, and back to Wright’s Fallingwater House and Chicago. I remember what a shock it was for us that Gusja’s relatives in Chicago lived much more modestly than we’d imagined. From Chicago we went west to Seattle, through the whole of Montana. We also went to see Vancouver, and along the west coast to Los Angeles. When we did a recap of our trip, we found that we had seen 51% of all the national parks and met many people. In Chicago, we met Mies van der Rohe, among others.

I might also mention my observation about Professor Ravnikar’s open-mindedness and breadth: we did not meet a single professor at any college in the USA who had such a range of interests, depth of thinking and, above all, the ability to do something, wissen und können, as they say. To know and also to be able to do something.

During your studies and in the early years of your practice, you established genuine collegial ties with some architects, which developed into friendships. I’m thinking of Oton Jugovec, Ilija Arnautović, Grega Košak, Saša Maechtig jr., and others. If I’m not mistaken, you worked with Oton Jugovec on a project in his office.

Jugovec and I worked together on a competition for the main Yugoslav university library in Belgrade. We drew and submitted the project from his place in the basement. We didn’t get anything in the end, but the experience was more than interesting. That was also my only collaboration with Jugovec, I didn’t help him with any of his realised projects. But we hung out a lot. Jugovec was a master of detail. He had this knack of how to do something from before. He could have been a watchmaker, and if he’d been in Switzerland he’d certainly have been a millionaire, because he would have invented a new watch.

The nice thing about the seminar at the faculty was that it didn’t matter whether Ravnikar came to you every day, which of course couldn’t happen. You could ask the person next to you everything, and if they didn’t know, you could go to someone else. People with different experiences, interests and abilities were there. Ilija Arnautović had already been in Prague in 1947, and he brought a lot with him. We would discuss all sorts of things, not just the details of how to tackle something. There were also various groups outside the faculty, and some were designing the posters for Cockta – Uroš Vagaja, Svetozar Križaj and others.

The complete interview is published in Winter 2021 issue of Piranesi No. 44-45/Vol. 29.